|

Estimating the Size of the Meteorite and Energy Applied to the Crust

John Michael Fischer, 2006 - 2026

www.newgeology.us

Summary

A

44-mile-diameter chondritic meteorite travelling at 20 km/sec impacting

at a 30 degree angle would produce

sufficient kinetic energy to drive all the landmasses on Earth

that moved, sliding away

from the impact with near zero friction as described by the Shock

Dynamics geology theory. Even though much of the surrounding continental

crust was expelled, enough indicators remain to guage a crater

size of 1000 km (621 mi) see "Ground

Zero". A theoretical model derives the same energy

level for the impact parameters, as does a formula used to predict

crater size from underground nuclear tests for a 1000 km crater.

Because the Shock Dynamics meteorite penetrated the crust

into the upper mantle, it should be treated as an underground

detonation. And while the type of blast ejecta suggests

it was a chondritic meteorite, values for an iron/nickel composition

are also included below.

Introduction

On June 30, 1908, a meteor exploded in the air over

Siberia. More than 300,000 acres of pine forest were leveled

in an instant. The Tunguska event is thought to have been

caused by a 50 to 60 meter diameter object exploding 8 kilometers

above the ground. Whether it was the fragment of an icy comet

or a rocky meteor, the energy of the blast is estimated to have

been between 10 and 20 megatons of TNT; equivalent to a hydrogen

bomb.J Larger and denser

objects reach the Earth's surface and penetrate, often to a depth

equal to their diameter. The densest meteorites, iron-nickel

type, weigh 7.8 grams per cubic centimeterK

(g/cm3), compared to upper continental crust density of 2.67L

g/cm3. The typical speed of an impacting meteorite is in the

vicinity of 20,000K meters per

second (m/s), or 44,740 miles per hour. For comparison, the

velocity of artillery shells is generally between 300

and 1000 m/sN.

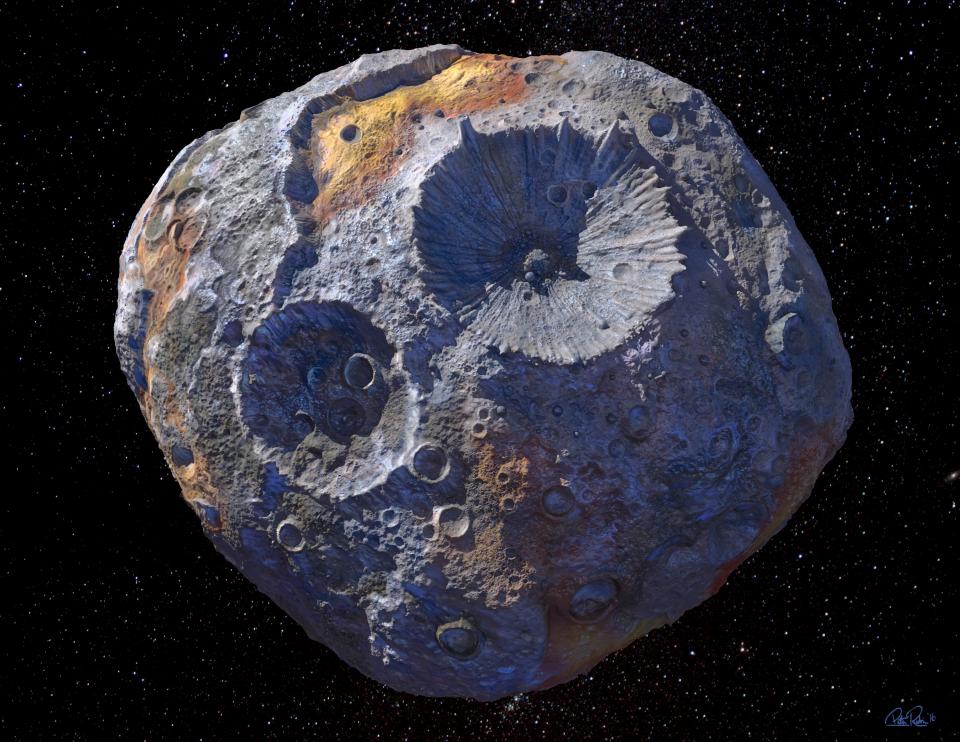

Psyche

is an iron/nickel asteroid over 200 km (120 mi) in diameter,

orbiting

between Mars and Jupiter

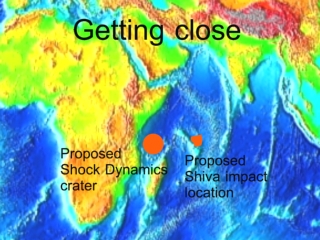

If you have reviewed the presentation at the www.newgeology.us website, you have seen that the arrangement of continents, mountain ranges, and trenches is completely explained as the consequence of a single explosion in the proto-continent north of present day Madagascar. This is not at all what one would expect given our current understanding of physics. Blast effects and pressure waves should dissipate rapidly away from the impact site, and continents should not budge. Yet the event was on a scale vastly larger than humans have ever experimented with. As mentioned in the website, experience with comparatively smaller events (though still large for humans) such as earthquakes, complex craters, and long-runout landslides suggests that a change occurs in the rheological properties of the crust at large scales of energy and mass. Continents slide smoothly as if on ice, while pressure and shear waves propagate unattenuated for thousands of miles. The apparent sudden freezing in place of these elements at the end of the event indicates a distinct threshold energy for such effects. As unpalatable as this seems, the flawless fit of crustal features with the shock dynamics scenario leaves us with no other choice.

Energy estimates

The apparent "superfluid" nature

of large-scale crustal physics makes calculating the forces involved

in setting the continents in motion simply a matter of transmitting

the kinetic energy of the meteorite to the crust to set the pieces

in motion. Based on the shock dynamics scenario, the meteorite

struck at an angle (from the ground) of 30 degrees, azimuth 93 degrees. It

had a density of 7.8 g/cm3 if

iron/nickel, or 3.35 g/cm3 if

chondritic, and a velocity of 20 km/s. The diameter

will

be calculated below. The greatest part of the explosion

struck the smaller, "East block" of continental crust.

All of the East block collided with Asia, and while Australia

and a number of islands rolled off farther to the east, they lost

momentum in the collision. The computer animation shows that

parts of the East block (New Zealand, Philippines, Australia)

interacted with the crustal wave. This indicates that these pieces of

continental crust, and therefore the whole East block before it

shattered, slid at surface wave velocity, about 150 m/sM.

This is considerably slower

than P (pressure) body waves, which pass through the interior of

the Earth at 8000 to 14000 m/s. However, Rayleigh surface

waves, like ocean waves, travel at near shear wave velocities that

are dependent on wavelength and the medium they travel through. Shear

wave velocities in sediments are quite low, such as 20 m/s in high

porosity clay or 50 m/s in sandy sediment.O

An ideal tsunami ocean wave, in waters 7000 m deep, wavelength

282 km, travels at 943 km/hr or 262 m/s. Because the energy

in the shock wave was far above that needed to fluidize the crust,

it passed through the crust as a fluid medium, similar to a tsunami

wave in waters 2000 m deep, wavelength 151 km, and velocity 504

km/h or 140 m/s. Also, body wave energy falls off at a rate

of 1/r2

since it is an expanding sphere, whereas surface wave energy falls

off much more slowly, at a rate of 1/r since it is an expanding

circle. A study of three powerful tsunamis in the PacificQ

concluded that "shorter-period waves attenuate much faster

than longer-period waves". The wavelength resulting from

the giant impact would have been extremely long. Thus the

crustal Rayleigh wave travelled far from the impact

site before the shock energy fell below the fluidizing level, and

the wave froze in place. The potential distance travelled by

all pieces of the

East block are assumed to have been the same as the unimpeded

portion of the crustal wave that ended as the Tonga-Kermadec Trench. Measurement of distance was made

from the east edge of the crater to the trench. Crustal thickness is 35

km, and overall crustal density is 1/3 of upper crust density (2.67

g/cm3) and 2/3 of lower crust density (2.9 g/cm3)L,

making it 2.82 g/cm3.

East block componentsL |

km2 |

|

Australia |

7,686,850 |

|

Bangladesh |

143,998 |

|

Bhutan |

47,000 |

|

Nepal |

140,797 |

|

Burma |

676,577 |

|

Thailand |

513,113 |

|

Laos |

236,800 |

|

Vietnam |

329,556 |

|

Kampuchea |

181,035 |

|

Malaysia |

332,632 |

|

Indonesia |

1,919,270 |

|

Philippines |

300,000 |

|

Papua New Guinea |

462,840 |

|

New Zealand |

269,057 |

|

Sri Lanka |

65,000 |

|

Pakistan |

828,453 |

Total:

17,336,953 km2

Potential East

block

travel distance (crater edge to Tonga Trench): 12,900 km

Kinetic energy (KE) of East block:

17,336,953 km2

x 35 km = 6.0679 x 108 km3

= 6.0679 x 1023 cm3

6.0679

x 1023 cm3 x 2.82 g/cm3 = 1.7111

x 1024 g = 1.7111

x 1021 kg

Rayleigh

wave moving

through the crust at 150 m/sM,

KE = 1/2 mass

x velocity2 so .5 x (1.7111

x 1021 kg) x (150 m/s)2

= 1.925 x 1025

Joules

KE of West block

The West block was much more massive

than the East block. When a large ball is hit with the same

force as a small ball, the large ball moves more slowly. So

the West block would have moved slower, but how much? All

other things being equal, a comparison of distances travelled versus

velocity is a reasonable measure. The East block would have

travelled 12,900 km (measured from the crater to the Tonga-Kermadec

Trench),

with a velocity of 150 m/s. The distances travelled by components

of the West block are shown below. Because of the significant

rotation of South America, the northern and southern halves are

listed separately.

| West block components |

(km2)L |

Distances travelled (km) |

| North America |

24,360,000

-- 1,527,470 (Alaska |

5843 |

Note: The Shock Dynamics scenario has East Antarctica as an island south of the protocontinent before the impact - not in the West block.

|

Determining the velocity of each component by comparison to East block potential distance/velocity: |

12900 km |

= |

5843 km |

and applying the equation KE = 1/2 mass x velocity2 to each part gives us

|

|

Velocity |

Mass* |

KE |

North America |

68 m/s |

2.5204 x 1021 kg |

5.8272 x 1024 J |

|

Northern S. Am. |

63 m/s |

1.3142 x 1021 kg |

2.6080 x 1024 J |

|

Southern S. Am. |

76 m/s |

4.4546 x 1020 kg |

1.2865 x 1024 J |

|

West Antarctica |

100 m/s |

3.8 x 1020 kg |

1.9 x 1024 J |

|

Greenland |

28 m/s |

2.1473 x 1020 kg |

8.4174 x 1022 J |

*Mass = km2 x 35 km x 2.82 g/cm3 x 1012

The total mass for the West block is 5.497 x 1021, and the KE is 1.171 x 1025 Joules

Diameter of the

meteorite

As

an imperfect elastic collision, the efficiency of the transfer of momentum from meteorite to target

is

generally quoted as 90%K,

but

25% is used here (Ef) as a conservative estimate of that part of the overall energy directed laterally.

Meteorite velocity is 20 km/s. Meteorite density is

7.8 g/cm3

iron/nickel or 3.35 g/cm3 chondritic. Vol = meteorite volume

in km3. Vertical high velocity

impacts form a shock wave in the target that is equal in all directions.

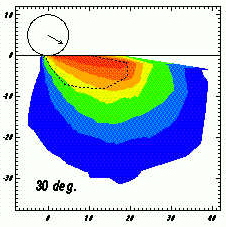

An impact at 30 degrees from the ground, as postulated for the Shock

Dynamics event, distributes the energy unevenly, with most in the

downrange (forward) direction, and the least to the sides and uprange

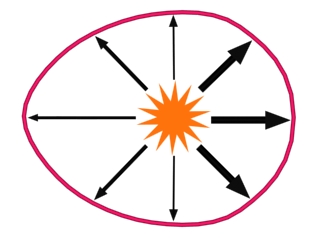

(back). The left image is a side-view cross section; on the

right is the view from above, with arrow thickness indicating strength.

|

From

- E. Pierazzo, H.J. Melosh. 2000.

"Melt production |

The combined KE required to move the two blocks is (1.925 x 1025) + (1.171 x 1025) = 3.096 x 1025 J. Using 1/2 m x v2, KE of the meteorite is 1/2 its mass x (20 km/s)2. The efficiency of the imperfect elastic collision is conservatively estimated at .25 transfer of KE to the crust. The first calculation is for a chondritic meteorite, the second for an iron/nickel meteorite:

1)

3.096 x 1028 g(m/s) = 1/2

meteorite mass x (20 x

103)2

m/s x .25 Ef.

There are 1 x 1015

cm3

in a km3,

so a density of 3.35 g/cm3

gives us

3.096 x 1028 g(m/s) = 1/2(Vol km3

x 3.35 x 1015

g/cm3) x

4.0 x 108

m/s x .25,

yielding 1.848 x 105

= Vol km3.

Assuming for simplicity a spherical bolide,

volume of a sphere is

4/3 pi r3,

4/3 pi r3

= Vol km3, so

1.848 x 105 km3

= 4/3 pi r3

r3 = 4.412 x

104 km3

r = 35.34 km, so if

it was a chondritic meteorite,

the diameter

was 2r, or 70.68 km

(43.92 miles) and

total impact energy is 1.238 x 1026

Joules = 2.96 x 1010 megatons of

TNT.

2)

3.096 x 1028 g(m/s) = 1/2

meteorite mass x (20 x

103)2

m/s

x .25 Ef.

There are 1 x 1015

cm3

in a km3,

so a density of 7.8 g/cm3

gives

us

3.096 x 1028 g(m/s) = 1/2(Vol km3

x 7.8 x 1015

g/cm3) x

4.0 x 108

m/s x .25,

yielding 7.937 x 104

= Vol km3.

Assuming for simplicity a spherical bolide,

volume of a sphere is

4/3 pi r3,

4/3 pi r3

= Vol

km3, so

7.937 x 104

km3

=

4/3 pi r3

r3 = 1.895

x 104

km3

r = 26.66 km, so if

it was an iron/nickel meteorite,

the diameter

was 2r, or 53.32 km

(33.13 miles) and

total impact energy is 1.238 x 1026

Joules = 2.96 x 1010 megatons of

TNT.

For comparison, estimated

parameters

of the Chicxulub impact are:

bolide diameter 10.6 to 80.9 km, mass

1.0 x 1015

to 4.6 x 1017

kg, yielding kinetic energy at 1.3 x 1024

Joules to 5.8 x 1025

JoulesR,

which is one to two orders of magnitude less.

While these estimates are only approximations, they do show how a moderately large meteorite with a typical velocity would have had the necessary kinetic energy to accomplish the actions described in the Shock Dynamics scenario. Also, while the mass of the West block is over 3 times larger than the East block, its components travelled much shorter distances, in accordance with an oblique impact that directed its energy (61%) to the east. It flung Australia all the way to the Pacific and plunged India/Southeast Asia into Asia, raising the largest mountains in the world. Clearly a central force divided the protocontinent, not random drift as claimed by Plate Tectonics.

Formula used with

U.S. underground nuclear

weapons tests - crater size and blast energy

Source: U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment, The Containment of Underground Nuclear Explosions, OTA-ISC-414 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, October 1989), 80 pages.

"The radius r (in feet) of the cavity is proportional to the cube root of the yield y (in kilotons):

For example, an 8-kiloton explosion would be expected to produce an underground cavity with approximately a 110-foot radius." (page 37)

"At first, the explosion creates a pressurized cavity filled with gas that is mostly steam. As the cavity pushes outward, the surrounding rock is compressed. Because there is essentially a fixed quantity of gas within the cavity, the pressure decreases as the cavity expands. Eventually the pressure drops below the level required to deform the surrounding material. Meanwhile, the shock wave has imparted outward motion to the material around the cavity." (page 34)

Applying the formula to the Shock Dynamics crater: 311 miles x 5280 feet = 1642080 feet,

1642080 divided by 55 = 29856,

298563 = 2.6613063 x 1013 kilotons or 2.6613063

x 1010 megatons of

TNT.

We see that the estimated force needed to impel the landmasses without friction in the Shock Dynamics scenario is very close to the predicted explosive force needed to form the Shock Dynamics crater: 2.96 x 1010 versus 2.66 x 1010 megatons of TNT.

Estimating meteorite

diameter from crater size, theoretical

It is interesting

to see the results from an interactive website sponsored by

Imperial College of London and Purdue University. The Earth

Impact Effects Program, by Robert Marcus, H. Jay Melosh, and Gareth

Collins, allows us to input parameters and view the calculated estimate.

The observed diameter of the Shock Dynamics crater is about 1000 km (622 miles) see "Ground Zero".

For a chondritic meteorite with 70.7 km diameter, 3500 kg/m3 density, 20 km/sec velocity, 30 degree impact angle, and 2750 kg/m3 target density, the final crater is 600 km (373 mi) across and 2.03 km (1.26 mi) deep. To make a 1000 km-wide crater the chondritic meteorite would need a diameter of 126 km (78 mi).

For an iron/nickel meteorite with 53.32 km diameter, 7800 kg/m3 density, 20 km/sec velocity, 30 degree impact angle, and 2750 kg/m3 target density, the final crater is 633 km (393 mi) across and 2.06 km (1.28 mi) deep. To make a 1000 km-wide crater the iron/nickel meteorite would need a diameter of 90 km (56 mi).

According to their formula, the explosive force of these meteorites would yield 3.09 x 1010 megatons of TNT (chondritic) and 2.96 x 1010 megatons of TNT (iron/nickel), which is essentially the same result from the formula used with U.S. underground nuclear weapons tests.

But unlike the underground nuclear test formula, this theoretical calculation appears to have been crafted without consideration for the depth of the explosion. The Shock Dynamics meteorite exploded at a depth roughly equal to its diameter, which was greater than the ~35 km-thick continental crust, so scaling its effects with the underground test formula is the better approach for estimating its crater size.

Let's see how the program deals with the much smaller "Meteor Crater" (Barringer Meteorite Crater), a surface impact in Arizona. Plugging in a meteorite with 40 m diameter, 7800 kg/m3 density, 12.8 km/sec velocity, 45 degree impact angle, and 2500 kg/m3 target density, the calculated final crater is 1.11 km (0.689 mi) across and 236 m (775 feet) deep. The actual crater is 1.2 km (0.739 mi) across and 170 m (560 feet) deep.

Largest

piece of the iron/nickel meteorite that formed Meteor Crater, Arizona

Shiva crater

|

|

|

Researchers think they have found the largest crater on Earth on the west coast of India. They believe the so-called Shiva crater was made next to the Seychelles (as shown at left) and moved north with India. They estimate that the meteorite was about 40 km in diameter. Because of their close proximity, the Shiva impact and the Deccan Traps (flood basalts) may be related. |

* * *

* * * * *

References

J Vitaly V. Adushkin and Ivan V. Nemchinov, "Consequences of Impacts of Cosmic Bodies on the Surface of the Earth", Hazards Due to Comets and Asteroids, ed. Tom Gehrels (Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1994), p. 722.

K H. J. Melosh, Impact Cratering - A Geologic Process. Oxford University Press, New York, 1989.

L The Great Geographical Atlas. Rand McNally & Co., 1982.

M Ralph B. Baldwin, "On the tsunami theory of the origin of multi-ring basins", Multi-ring Basins, Proceedings of the Lunar and Planetary Science Conference (1981), 12A, pp. 275-288.

M Ralph B. Baldwin, "The Tsunami Model of the Origin of Ring Structures Concentric with Large Lunar Craters", Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors, Vol. 6, 1972, pp. 327-339.

M W. G. Van Dorn, "Tsunamis on the moon?", Nature, Vol. 220, 1968, pp. 1102-1107.

M Freeman Gilbert, "Gravitationally perturbed elastic waves", Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, Vol. 57, No. 4, 1967, pp. 783-794.

N Ian V. Hogg, The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Artillery. Chartwell Books Inc., 1988.

O Michael D. Richardson, Enrico Muzi, Luigi Troiano, "Shear wave velocity in surfictal marine sediments: A comparison of in situ and laboratory measurements", The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, Vol. 83, Issue S1, May 1988, p. S78.

P Matthias A. Meschede, Connor L. Myhrvold, Jeroen Tromp. 2011. Antipodal focusing of seismic waves due to large meteorite impacts on Earth. Geophysical Journal International, Vol. 187, pp. 529-537.

Q Rabinovich, Alexander B., Rogerio N. Candella, Richard E. Thomson. 2013. The open ocean energy decay of three recent trans-Pacific tsunamis. Geophysical Research Letters, Vol. 40, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.1002/grl.50625.

R Durand-Manterola, Hector Javier, Guadalupe Cordero-Tercero. 2014. Assessments of the energy, mass and size of the Chicxulub Impactor. arXiv:1403.6391